Secret Meeting score: 88

by Phil Scarisbrick

“Well, as you might know, he’s been in the studio for the last two weeks with someone else. It’s working out well so we won’t be needing you. He’s very sorry.”

Tony Visconti had worked with David Bowie on his previous four studio albums (Scary Monsters (And Super Freaks), Lodger, “Heroes” and Low), as well as three other albums from earlier in his career. He had set time aside to work on the next project but he was getting slightly perplexed at the lack of details that were forthcoming from the Bowie camp. He rang Coco – Bowie’s personal assistant – to find out what was happening. This was when he found out that his services wouldn’t be required on this record. Bowie’s decision to cast his long-time collaborator and friend aside, as well as the manner in which the information reached Visconti, caused a fracture in the pair’s relationship that meant they didn’t work with each other again for two decades.

The “someone else” that Coco had referred to was Chic co-founder and one of the most prolific producers of the era, Nile Rodgers. He had such a knack for creating hits that his trusty Fender Stratocaster had been nicknamed ‘The Hitmaker’. By the start of the eighties, his work with Chic had slowed down, allowing him to spend more time producing other acts. He’d had a worldwide hit with Sister Sledge’s We Are Family, and this kind of success was attracting some of the biggest names in the industry into wanting to work with him. He’d go on to have huge success with the likes of INXS, Madonna and Duran Duran, but before all that, the seventies’ biggest star needed his assistance.

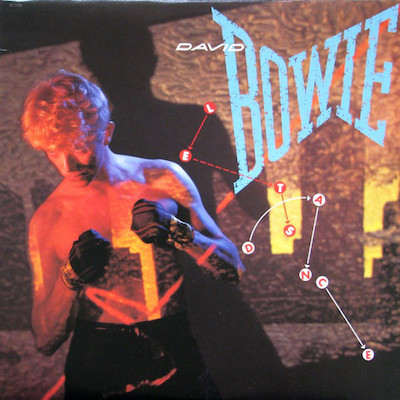

‘Chameleonic’ is one of those rock’n’roll clichés that get needlessly bandied about when somebody decides to throw a synth solo on a rock album, or add a bit of reverb to a vocal where otherwise they wouldn’t. One man truly embodied that label though. Since his 1969 eponymous second album, David Bowie had been on a journey that had seen him embody a myriad of characters and personas, as well as creating some of the greatest records in popular music history. In fact, Rolling Stone magazine described Let’s Dance as “the conclusion of arguably the greatest 14-year run in rock history.” While that description was complimentary, the label of ‘rock’ completely undersold what Bowie had done in this period. He’d leapfrogged from genre to genre, often transcending whatever label people tried to stitch to his latest project.

By the start of the eighties, Bowie had left RCA Records and signed a reported $17.5 million deal with EMI. With such a huge investment made in him, a quick return would only be achievable with commercial success. The decision to draft in Rodgers to co-produce the record was a shrewd move given his hit-making experience, and especially as Bowie intended it to be “a rediscovery of white-English-ex-art-school-student-meets-black-American-funk” he’d first delved into with 1975’s Young Americans. In preparation for the album, Bowie spent three days laying down demos to take to the studio, something he’d rarely done for his preceding records. The weight of expectation clearly focussed him into leaving no stone unturned.

Sessions took place at the Power Station studio in Manhattan over 17 days (including mixing). With Bowie performing nothing but vocals on the album – a rarity for him – he drafted in other musicians to play for him. Up-and-coming blues guitarist, Stevie Ray Vaughan, was given the six-string duties after Bowie had been impressed with his performance at the 1982 Montreaux Festival. Describing the sessions, Vaughan explained how Bowie gave him the creative freedom to express himself, “David Bowie is real easy to work with. He knows what he’s doing in the studio and he doesn’t mess around. He comes right in and goes to work. Most of the time, David did the vocals and then I played my parts. A lot of the time, he just wanted me to cut loose. He’d give his opinion on the stuff he liked and the stuff that needed work. Almost everything was cut in one or two takes. I think there was only one thing that needed three takes.”

The album’s title track is one of the most successful singles Bowie ever released, reaching No. 1 in the UK and USA. It is a song that achieved exactly what Bowie had set out to when he hired Rodgers. The original demo of Let’s Dance was described by Rodgers as being a “folk song”, but by inverting the basic tune, adding upstrokes and changing the key, he was able to evolve the song into something that “the entire world would soon be dancing to”, as well as providing the blueprint for the rest of the record. The ascending crescendo of ‘aah’s’ in the intro recall the energy and call-to-arms feel of The Beatles’ cover of Twist and Shout. Bowie’s decision to steer clear of playing instruments and focus on his vocals was a wise move. A timely reminder of just how great that voice was comes at the end of the chorus, as Bowie sings “If you should fall into my arms/And tremble like a flower” above a cacophony of ‘aah’s’, building on those we hear in the intro. To this day, it is one of Bowie’s best known and most instantly recognisable songs.

Opening track – Modern Love, is the perfect introduction to the “original party-funk cum big bass drum sound greater than the sum of its influences” sound of the record. Funky, muted guitar strokes give way to a bass-heavy drum sound that provides the dance-inducing quality that Bowie had strived for. A theme that runs throughout the album is the struggle between God and man, with Modern Love not only introducing the theme but also being its most overt reference as Bowie sings – “Modern Love gets me to the church on time”. The layered horns and vocal melodies, as well as a distinctive two-note piano hook, make Modern Love a poptastic album opener.

China Girl was originally recorded for Iggy Pop’s debut solo album, The Idiot. Co-written by Bowie and Pop, the song tells the tale of Iggy’s infatuation with a Vietnamese woman called Kuelan Nguyen. When Bowie decided to do a version of his own for Let’s Dance, he gave it to Rodgers to come up with a new arrangement. Whether he was unaware of the original meaning, or chose to ignore it, it isn’t clear. Explaining his interpretation, Rodgers said “I figured China Girl was about doing drugs, because China is China White which is heroin, girl is cocaine. I thought it was a song about speedballing. I thought, in the drug community in New York, coke is girl, and heroin is boy. So then I proceeded to do this arrangement which was ultra pop. Because I thought that, being David Bowie, he would appreciate the irony of doing something so pop about something so taboo. And what was really cool was that he said ‘I love that!’.” The oriental-sounding guitar hook adds a new layer of funk to the introduction, as well as providing the bedrock for the rest of the song. There is an odd juxtaposition of lyrics like “visions of swastikas in my head” being sung with such romanticised melodies, but it works beautifully.

Without You closes out the first side of the record with its odd, staccato rhythm sitting under a delicate, restrained lead vocal. A simple love song, it was the final single from the album and provides a respite from the in-your-face pop that inhabits the rest of Side A. It also features a cameo appearance from Rodgers’ Chic bandmate, Bernard Edwards on bass. Commencing Side B is Ricochet, recalling elements of Bowie’s Berlin era but with all the extra sheen that a Nile Rodgers production provides. Returning to the album’s biblical themes, he sings “Turn the holy pictures so they face the wall/And who can bear to be forgotten“. A wailing saxophone battles Stevie Ray Vaughan’s guitar for supremacy as the song builds in ferocity.

Criminal World is a cover version, originally released by the English band, Metro. Their version had been banned by the BBC due to its sexual content, a fate that didn’t stop Bowie putting his own stamp on the track. Stevie Ray Vaughan’s guitar again plays a prominent role on what would end up being the B-side to Without You. Cat People (Putting Out Fire) was originally written by Bowie as the title track for Paul Schrader’s film of the same name. Co-written with legendary producer, Giorgio Morodor, the original had been Bowie’s biggest hit since Golden Years. He’d planned to include the original version on Let’s Dance, but a contract dispute with Morodor’s label (MCA Records), meant that he was forced to re-record it. The version we got on the album though hugely benefitted from both Vaughan’s guitar playing and Rodgers’ production, with an energetic jam that is probably the highlight on the album’s B-side.

Although Let’s Dance was a huge commercial success, it was deemed musically lightweight by a lot of critics at the time. Because of the revolutionary way Bowie had approached music during the preceding 15 years, some felt like the decision to use Nile Rodgers was a cop out to chase commercial success. Looking back now, some 36 years after it was released, this analysis is deeply unfair. While the sound would go on to be a hallmark of eighties pop music, the album itself showcased Bowie’s ability to once again reinvent himself and inhabit new ground. Describing the album, Bowie said “at the time, Let’s Dance was not mainstream. It was virtually a new kind of hybrid, using blues-rock guitar against a dance format. There wasn’t anything else that really quite sounded like that at the time. So it only seems commercial in hindsight because it sold so many. It was great in its way, but it put me in a real corner in that it fucked with my integrity.”

While it may not have the theatrics of Ziggy Stardust, the technological experimentation of Low, or the dark brooding of “Heroes”, Let’s Dance provides a niche all of its own. By providing Bowie with some of the biggest hits of his career, it was a gateway to a new generation to be hooked onto one of popular music’s greatest stars. Even now, it lights up clubs and parties around the world, with its title track being sung verbatim by almost all who hear it. My four year old son loves it as much as I do, as much as my father does. While Bowie had a huge fan base already, no record he produced before or since crossed over to be so universally recognised. There are many elements that make it so adored. You have Rodgers’ production, Stevie Ray Vaughan’s guitar work and the arsenal of brass and synths that light up the album. But do not let this detract from the fundamental element makes it so special: David Bowie. So today, drop the needle on this fine record, put on your red shoes, and dance the blues.